Straight Healthcare Medical Study Analysis CME

5 AAFP credits - $40

- Review the course objectives and outline and read excerpts from the program. Learn how to interpret medical studies and apply study measures using commonsense concepts.

- Purchase Medical Study Analysis CME for $40 and earn 5 AAFP credits upon completion (see AAFP credit acceptance)

- If you have purchased the CME or are an annual Straight Healthcare subscriber, please ensure you are logged in to your account. You can then use the link to access the material and tests.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE MEDICAL STUDY ANALYSIS CME

COURSE OBJECTIVES

Every month, hundreds of studies are published in medical journals. Some are practice-changing, while many offer little value other than a credit in the author's bio. Sifting through the barrage of trials, guidelines, analyses, and reviews to find meaningful content can be difficult. It's more important now than ever that providers understand the principles of quality medical research and sound statistical techniques so they can decipher which information will improve their outcomes. After completing this program, providers will be able to:

- Define the four main types of medical studies, including their strengths and weaknesses

- Identify confounding and different types of bias

- Explain basic statistical concepts, including the normal distribution, confidence intervals, p-values, and study power

- Define different types of outcome analysis and recognize the problems with each

- Interpret and apply study measures, including relative and absolute risk, sensitivity, and specificity

COURSE OUTLINE

- INTRODUCTION

- OBJECTIVES

- ACRONYMS

- STUDY TYPES

- Introduction

- Randomized controlled trials

- Randomization

- Blinding

- Procedural studies

- Unblinding by treatment effects

- Blinding index

- Observational studies

- Cohort studies

- Case-control studies

- Advantages

- Disadvantages

- Confounders

- Selection bias

- Surveillance bias

- Protopathic bias

- Reverse causation

- Causality

- Meta-analysis

- Advantages

- Disadvantages

- Example

- Network meta-analysis

- Quasi-experimental design and Natural experiments

- STATISTICAL THEORY

- The normal distribution

- 95% Confidence Interval

- The p-value

- Statistical significance

- Multiple comparisons

- STUDY DESIGN

- Introduction

- Study power

- Outcome analysis

- Intention-to-treat analysis (ITTA)

- Per-protocol analysis (PPA)

- Patient adherence

- When PPA matters

- As-treated analysis (ATA)

- On-treatment analysis (OTA)

- Modified ITTA

- Noninferiority outcomes

- ABSOLUTE VS RELATIVE RISK

- SENSITIVITY AND SPECIFICITY

- Definitions

- PPV / NPV

- Interplay between the two

- OTHER

- Recall bias

- Reporting bias

- Sensitivity analysis

- Bayesian theory/inference

- Cluster randomization

- Pragmatic trials

- Propensity score matching

EXCERPT #1

SENSITIVITY AND SPECIFICITY

Doctors order a lot of tests, many of which have a sensitivity and specificity for some condition. On the surface, these terms seem self-explanatory. If a test is sensitive, it's usually positive if a condition is present. If a test is specific, a positive test makes the condition very likely. Most people understand these concepts, but applying the information can sometimes be confusing. To illustrate, I'm going to present you with a clinical scenario.

A very distraught 52-year-old female comes to see you in your clinic. Your colleague ordered a Cologuard test on her, and it came back positive. Someone from your office called her and gave her the results, and since then, she has been unable to sleep and having daily panic attacks because she is afraid she is going to die from colon cancer. She tells you she went to the Cologuard website and read that the test has a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 90%. She starts to cry hysterically and says, "That means there is only a 10% chance the test is wrong."

So what do you want to tell her? Does she really have a 90% chance of having colon cancer? Let's break these two measures down and see if we can give her an educated answer.

First, let's tackle sensitivity, defined as the percentage of people with the disease who get a positive result. If a test has high sensitivity, almost everyone with the disease will have a positive test. Cologuard has a sensitivity of 92%, which means only 8% of people with colon cancer will get a negative result (false negatives). Tests with high sensitivity are most useful when negative because it means the disease is very unlikely. The significance of a positive result depends on the specificity.

Specificity is the percentage of people without the disease who get a negative result. Cologuard has a specificity of 90% which means only 10% of people without colon cancer will get a positive result (false positives). A test with high specificity is most useful when positive because it makes the disease likely. The illustrations below help to explain the relationship. [71]

EXCERPT #2

SELECTION BIAS

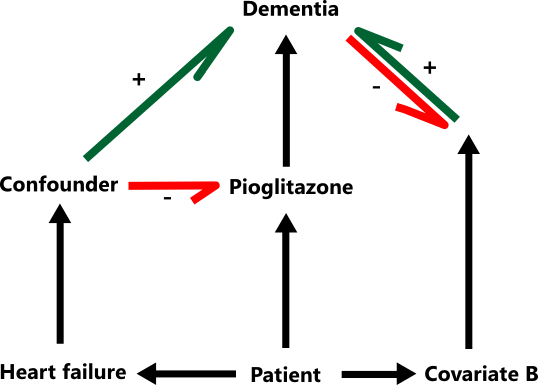

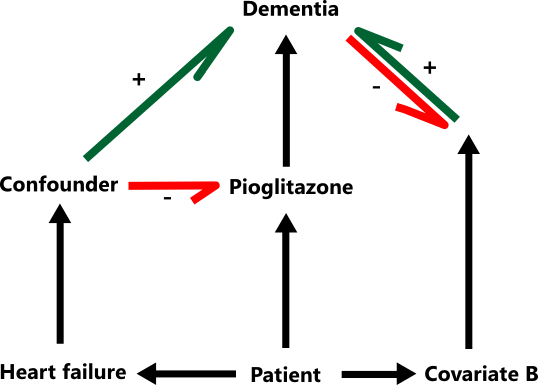

To illustrate selection bias, let's discuss a study involving pioglitazone (Actos). Pioglitazone is an insulin sensitizer like metformin that lowers blood sugars without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia, making it a popular drug 10 to 20 years ago. However, it does have one nasty side effect: fluid retention. In studies, up to 30% of heart failure patients experienced worsening symptoms while taking it, and after it had been on the market for a while, a contraindication in NYHA class III and IV heart failure was added to the labeling.

In a recently published cohort study, Korean researchers used a medical database to compare the incidence of dementia between diabetics who took pioglitazone and those who did not. After examining data from 91,218 patients over 10 years, they found dementia risk was significantly lower in patients who received pioglitazone (HR 0.84, 95% CI, 0.75-0.95). [55] This study received a fair amount of press, and if you Google "pioglitazone and dementia," pages of results will come up about these findings. So, should everyone over fifty take pioglitazone? I would argue no because these results are likely due to selection bias.

Consider the following: the two most common causes of dementia are Alzheimer's disease and cerebral atherosclerosis, which causes vascular dementia (strokes, cerebral ischemia). The most common cause of heart failure is ischemic heart disease, also caused by atherosclerosis. Taken together, it is easy to see that patients with heart failure are more likely to have atherosclerosis, which also increases their risk of vascular dementia. [57]

Now back to our study. As we discussed earlier, pioglitazone and weak hearts do not mix well, so it is less likely to be prescribed to patients with heart failure. This is selection bias, and it indirectly reduces pioglitazone's association with vascular dementia. In their conclusion, the authors claim that pioglitazone can "

suppress dementia in patients with DM," but buried deep in the paper, they admit the possibility of selection bias. And in case you were wondering, a RCT comparing pioglitazone to placebo for dementia prevention has been performed, and it was stopped early due to futility. [56]

In our confounder model, heart failure is the confounder because it reduces the likelihood of the exposure (pioglitazone) and increases the probability of the outcome (dementia).

AAFP CREDIT ACCEPTANCE

The AAFP has reviewed this program and deemed it acceptable for AAFP credit.

Providers should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their

participation in the activity.

AMA/ AAFP Prescribed credit is accepted by the American Medical Association as

equivalent to AMA PRA Category 1 credit(s)™ toward the AMA Physician's Recognition

Award. When applying for the AMA PRA, Prescribed credit earned must be reported as

Prescribed, not as

Category 1

AAFP Prescribed credit is accepted by the following organizations:

- American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA)

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA)

- American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC)

- American Academy of Nurse Practitioners Certification Board (AANPCB)

- American Association of Medical Assistants (AAMA)

- American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM)

- American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM)

- American Board of Preventative Medicine (ABPM)

- American Board of Urology (ABU)