Population-based MRI study finds rotator cuff abnormalities in nearly all adults over 40, with poor correlation to symptoms

The issue: Shoulder pain is a common complaint, and imaging is frequently ordered

Why this study matters: It evaluated the prevalence of rotator cuff abnormalities on MRI in the general population and found that they are common in asymptomatic people.

Primary care relevance: Highlights the hazard of over-imaging: incidental findings are common in asymptomatic people and may lead to unnecessary treatment or surgery; routine MRI for atraumatic shoulder pain has limited value.

Individual-patient-data meta-analysis finds no benefit of beta-blockers after MI in patients with preserved ejection fraction

The issue: Four large trials evaluating the benefits of beta-blockers in post-MI patients with preserved LVEF came to different conclusions

Why this study matters: It combines data from the trials and offers an estimate of the overall effect of beta-blockers in this patient population.

Primary care relevance: Supports reassessing the need for long-term beta-blockers in post-MI patients with preserved EF.

Tradipitant (Nereus®), an NK-1 receptor antagonist, is the first drug in its class approved for the prevention of motion sickness

The issue: Motion sickness is a common problem that affects many people, especially travelers.

Why this matters: Tradipitant (Nereus®) is a new drug for motion sickness prevention with a novel mechanism of action.

Primary care relevance: Offers a new prescription option for motion sickness prevention with a different mechanism than scopolamine or antihistamines.

Randomized trial finds 15% dose increase when taking levothyroxine with breakfast maintains TSH stability

The issue: Food reduces the absorption of levothyroxine (LT4); therefore, dosing guidelines recommend taking it on an empty stomach, typically 30 to 60 minutes before breakfast. Many patients find this inconvenient.

Why this study matters: It randomized 88 adults with hypothyroidism to fasting LT4 intake or LT4 intake with breakfast with a 15% dose increase. The primary outcome, TSH stability, did not differ significantly between groups.

Primary care relevance: For patients who prefer taking LT4 with food, this study provides guidance on dose adjustment.

The vaccine had a significant effect but no meaningful overall benefit

The issue: Several RSV vaccines for adults have been developed in recent years and are heavily marketed to seniors, but data on their real-world effectiveness against hospitalization are limited.

Why this study matters: The DAN-RSV open-label trial randomized 131,276 adults 60 years and older to RSVpreF vaccine (Abrysvo®) or no vaccine; hospitalization for RSV-related respiratory tract disease occurred in 3 vs. 18 participants (vaccine effectiveness, 83.3%; P=0.007).

Primary care relevance: The study primarily showed that RSV does not appear to be a significant cause of respiratory illness in older adults; the NNT to prevent one RSV hospitalization was approximately 4400, indicating minimal individual benefit.

PISCES trial finds fish oil reduces cardiovascular events in hemodialysis patients

The issue: Large trials of fish oil for CVD prevention have yielded conflicting results; REDUCE-IT showed benefit while STRENGTH did not.

Why this study matters: The PISCES trial randomized 1,228 hemodialysis patients to fish oil 4 g daily or corn-oil placebo; fish oil reduced serious cardiovascular events by 43% (HR 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47 to 0.70; P<0.001) over 3.5 years.

Primary care relevance: PISCES aligns with REDUCE-IT but contradicts STRENGTH; the overall effects of fish oil on CVD remain inconclusive.

ESCUDDO trial finds single-dose HPV vaccination noninferior to two doses

The issue: Current guidelines recommend two doses of Gardasil 9 for adolescents; whether one dose provides comparable protection has been uncertain.

Why this study matters: The ESCUDDO trial randomized girls 12 to 16 years to one or two doses of bivalent (Cervarix) or nonavalent (Gardasil 9) HPV vaccine; one dose was noninferior to two doses for preventing HPV16 or HPV18 infection.

Primary care relevance: Supports WHO single-dose recommendation; study has limitations including 5-year follow-up and nonrandomized control group requiring propensity matching.

Recent studies show benefit in severe disease, but routine use remains unproven

The issue: Studies evaluating corticosteroids in CAP have produced mixed results; their role in routine practice is uncertain.

Why these studies matter: The SONIA trial showed reduced mortality with glucocorticoids in low-resource settings; the CAPE COD trial showed benefit in ICU patients.

Primary care relevance: The IDSA recommends against routine steroids in CAP; evidence supports use only in severely ill patients requiring ICU care.

Self-collection is convenient and time-saving for many women, but only one option exists for home collection

The issue: Cervical cancer screening has traditionally required an in-person visit and pelvic exam; that barrier contributes to underscreening, especially among people who lack access to gynecologic care or have difficulty scheduling visits.

Primary care relevance: Provides guidance on self-collected swabs for cervical cancer screening.

Retreatment reduces viral loads and symptoms by one day but shows no meaningful benefit on hospitalizations or deaths

The issue: Some patients experience COVID symptom rebound after completing Paxlovid; the safety and benefit of retreatment have not been studied.

Why this study matters: This study evaluated the safety and benefits of a second course of Paxlovid in patients with rebound COVID symptoms.

Primary care relevance: Provides guidance on whether to retreat COVID-19 patients experiencing rebound symptoms.

Zoliflodacin and gepotidacin offer oral alternatives to injectable ceftriaxone

The issue: Gonorrhea resistance to current therapies is increasing.

Primary care relevance: Providers now have two new oral antibiotics to treat gonorrhea, potentially improving treatment access and patient convenience.

Two randomized trials examine whether anticoagulation can be safely discontinued after successful catheter ablation

The issue: One-year success rates of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation range from 50 - 85% and decline over time. Many patients hope to stop anticoagulation after ablation, but the risks and benefits of this decision have not been clearly defined.

Why these studies matter: The ALONE-AF and OCEAN studies were designed to evaluate the risks and benefits of stopping anticoagulation after successful catheter ablation. They also provided guidance on what defines successful ablation.

Primary care relevance: The studies provide data for making an informed decision on stopping anticoagulation and determining which patients are candidates.

First oral GLP-1 receptor agonist approved for weight loss

The issue: Patients who dislike injecting themselves now have an FDA-approved oral GLP-1 receptor agonist option for weight loss.

Primary care relevance: Providers now have an oral option for patients who prefer not to use injectable GLP-1 therapy for weight management.

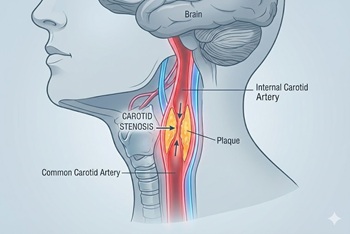

New randomized trial compares carotid stenting and endarterectomy to intensive medical management

The issue: In the U.S., most asymptomatic high-grade (≥70%) carotid stenosis is treated with revascularization (stenting or endarterectomy). However, the risks and benefits of this approach, and how it compares with contemporary medical therapy, have never been evaluated in a clinical trial.

Why this study matters: The CREST-2 study provides the first modern evidence comparing carotid stenting and endarterectomy to intensive medical management for asymptomatic carotid stenosis.

Primary care relevance: Providers now have good data to counsel patients on the risks and benefits of stenting, endarterectomy, and medical management of asymptomatic carotid stenosis.

DECAF trial challenges long-standing recommendations to avoid coffee

The issue: Patients with atrial fibrillation are routinely advised to avoid caffeinated beverages, but evidence supporting this recommendation has been inconsistent.

Why this study matters: The DECAF randomized clinical trial compared continuing caffeinated coffee consumption to abstinence in patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent successful electrical cardioversion.

Primary care relevance: Provides guidance on counseling patients with atrial fibrillation about coffee consumption.

Lynkuet joins Veozah as a nonhormonal option for vasomotor symptoms

The issue: Many women seek nonhormonal alternatives for menopausal hot flashes due to concerns about hormone replacement therapy.

Primary care relevance: Women now have two nonhormonal options for treating menopausal hot flashes, though both medications are more expensive than HRT and often require prior authorization.

Recent trials question routine long-term beta-blocker use after MI

The issue: Beta-blockers are routinely recommended for all post-MI patients, but this practice is based on trials predating modern revascularization and intensive secondary prevention.

Why this study matters: Four recent randomized trials have evaluated the long-term benefit of beta-blockers in post-MI patients with preserved LVEF.

Primary care relevance: Provides guidance on continuing beta-blockers in post-MI patients with preserved LVEF.

The HI-PRO trial randomized patients with provoked VTE and minor chronic risk factors to 12 months of apixaban or placebo after completing at least 3 months of anticoagulation.

The issue: Current guidelines recommend 3 months of anticoagulation for provoked VTE; the role of extended therapy in patients with ongoing risk factors is unclear.

Why this study matters: The trial evaluated the long-term benefit of extended anticoagulation in patients with provoked VTE and minor chronic risk factors.

Primary care relevance: Provides guidance on extending anticoagulation in patients with provoked VTE and minor chronic risk factors.

Study finds higher potassium targets are beneficial in patients with ICDs and CVD

The issue: Patients with ICDs and cardiovascular disease are at risk for ventricular arrhythmias; potassium levels may influence this risk.

Why this study matters: The trial evaluated the benefit of targeting high-normal potassium levels (4.5–5.0 mEq/L) in patients with ICDs and CVD.

Primary care relevance: Provides guidance on adjusting potassium supplements and medications in patients with ICDs and CVD.